Neil Hayward and Robert H. Stymeist

Eastern Bluebird. Photograph by Philip Kyle.

September and October 2018 will be remembered for the rain. And although it seemed like it was always raining, that didn't dampen the spirits of birders eager to enjoy the excitement of fall migration.

September temperatures in Boston averaged 69 degrees, four degrees above normal, with a high of 97 degrees on September 6. A total of 5.12 inches of rain was recorded in Boston during the month, nearly two inches above average, and areas to the west received even more. The remnants of Hurricane Florence arrived on September 14, bringing two inches of rain to Boston. Winds of up to 70 mph were recorded on the North Shore and microbursts caused roads to flood in a number of communities. Heavy rain, especially in central and western Massachusetts, fell again on September 25; Pittsfield recorded 4.2 inches, Orange nearly 3 inches, and Worcester 1.8 inches.

October was cooler, with temperatures in Boston averaging 54 degrees, which is normal for the month. The high was 86 degrees on October 10 and the low was 34 degrees. Rainfall in Boston totaled 3.78 inches with the highest 24-hour total of 2.22 inches falling on October 27–28. Powerful thunderstorms, delivering pea-size hail and high winds, downed trees and knocked out power to thousands just before the start of Game 1 of the World Series. Two funnel clouds (cone-or needle-like protuberances dropping from the main cloud base) were reported over the water in Sandwich.

R. Stymeist

GEESE THROUGH IBISES

A Ross's Goose, photographed in Salem on September 22, is the earliest winter record by three weeks, and the only September record for the state. This Arctic-nesting goose was first added to the state list in 1997 and has been annual since 2008. The increase in local observations reflects a shift eastward in their breeding range coupled with a major population increase (from about 100,000 birds in the mid-1960s to about 3 million today). Other goose highlights during the period included four records of Cackling Goose (about typical for the period) and a Greater White-fronted Goose in Hampden. Inland records of Brant are uncommon and a count of 65 at Quabbin Park on October 21 is notable.

An early female King Eider was photographed migrating with Common Eiders past Andrews Point, Rockport, on September 25. A limping Harlequin Duck at Plymouth on September 1 is the earliest returning winter record for Plymouth County. Redheads were noted in three counties, with the first October record for Berkshire since 2014. Wood Ducks are common breeders in Massachusetts; the Massachusetts Breeding Bird Atlas 2 counted them in 70 percent of blocks in 2007–2011. In the fall their numbers are boosted by migrants, although a count of 390 at Burrage Pond on October 24 represents an exceptionally large flock. Scoters are also on the move in October, when they are typically reported from inland locations. This year the numbers reflected the usual species abundance; Black Scoter is the most common inland, Surf Scoter the least common.

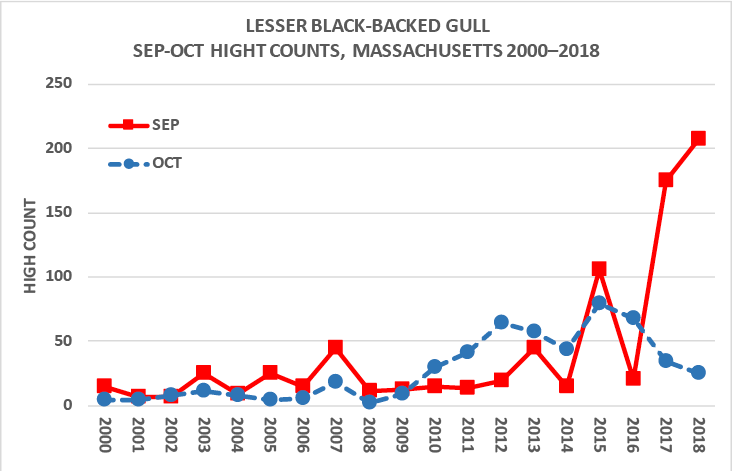

Figure 1. Fall high counts of Lesser Black-backed Gulls in Massachusetts, 2000–2018. Data from eBird.org.

Yellow-billed Cuckoos made the birding headlines this fall. With the exception of October 3–4, birds were reported every day throughout October. (Last year the species had departed the state by October 8.) Franklin and Hampshire Counties scored their first October records since 2011, and Worcester its first since 2010. Some of these cuckoos are local breeders, no doubt reflecting a good cuckoo year; the later ones are reverse migrants from the south. Chimney Swifts are on the same migratory schedule and are similarly uncommon after the first week of October. This year birds were recorded right up to the end of the month, a phenomenon last seen in 2005. Like the cuckoos, the swifts fell foul to periods of sustained southerly winds causing reverse migration, with southerly birds flying back north. Strong winds in the last few days of the month may also have delivered an unidentified Selasphorus species of hummingbird (Rufous or Allen's) to a feeder in Brewster.

At Fairhaven this summer an apparent female King Rail was observed copulating with a male Clapper Rail. In September, young rails were spotted being escorted by the King Rail. While it's possible the "King Rail" may have been an exceptionally bright Clapper, hybridizations between these two taxa are not uncommon, occurring in areas of intermediate salinity or where fresh water and salt water are in close proximity (Maley and Brumfield, 2013). Common Gallinules were reported from five counties this period, which is the second largest geographic distribution for the fall this century.

The shorebird highlight of the period was a Common Ringed Plover at South Beach, Chatham on September 2. This would represent the sixth record for the state, hot on the heels of the previous month's fifth record—also an adult male and also in Chatham (Monomoy). A Black-necked Stilt was also on Cape Cod, at Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary, on September 1. Piping Plovers were late to leave the state; a bird at Duxbury Beach on October 28 is the latest departure since 2011. And Purple Sandpipers were similarly late in their return to the state; the first report came from Plum Island on October 28, the latest winter arrival since 2007.

October was a very good month for alcids with multiple reports of Dovekie, Common Murre, and Razorbill. The three reports of Common Murre are the first October sightings since 2012, and a bird reported from Plum Island on October 11 would be the earliest recent winter record for the state, but for last year's September 23 sighting at Race Point. A report of 242 Razorbills at Andrews Point, Rockport, on October 27 beat the previous October record of 172 at the same location that was set a decade earlier. Single Atlantic Puffins were reported from Rockport in September and from Plum Island in October.

The larid highlight of the period was a new record count: 207. This was the number of Lesser Black-backed Gulls logged at Monomoy on September 17 and beats the previous high count of 190 birds set on Nantucket on January 1, 2010. Lesser Black-backs were once a rare vagrant to North America; the first record was from New Jersey in 1934. The recent and dramatic increase in local numbers (see Figure 1) is a result of a range expansion with breeding populations now established in Iceland (from the 1920s) and Greenland (from 1990). Apart from a handful of hybrid pairings with Herring Gulls, the species has yet to be documented breeding in North America. A juvenile Black-headed Gull at Winthrop was the first Suffolk County record since 2006. An adult Sabine's Gull at Race Point, Provincetown, is about average for the season.

Pacific Loon breeds in Alaska and Northwest Canada, with nests as close to Massachusetts as Hudson Bay. Despite a nontrivial separation from our more regularly seen loons, Pacific Loon is now found annually on our winter shores. The species has been reported every month of the year except for August. This year's early record of September 30, from Provincetown, is only the second record for September. A bird present in Wareham for two days in October is a first record for Buzzard's Bay.

An adult Brown Booby at Rockport on September 2 is the first record for Essex County. This has been a remarkable year for the species, with six records from five counties, including a well-chased bird inland in Berkshire County in August. Before this year, there were only about a dozen reports for the state. The increase in Brown Booby sightings in Massachusetts is part of a larger phenomenon in which this tropical sulid seems to be wandering farther north up the Atlantic Coast—as far as the north coast of Newfoundland (2012 and 2018) and inland to Lake Erie (2013).

Glossy Ibises first started breeding in the state in 1974. Since then, the population has increased, primarily in coastal Essex County. Inland sightings, however, remain rare. A single bird at Sheffield on October 6 represents the only October record for Berkshire County, whose previous late record was September 9.

N. Hayward

VULTURES THROUGH DICKCISSEL

The fall migration of hawks through our region gets underway in earnest during this period. The general consensus among local hawkwatchers was that this year's migration was poor. Numbers of Broad-winged Hawks in particular were down, especially at traditional flyover sites such as Wachusett Mountain in Princeton and Mount Watatic in Ashburnham. Hawkwatchers at Wachusett Mountain tallied only 5,042 Broadwings for the period, the lowest seasonal total since 2,364 in 2011. The peak day for Wachusett was September 22 when 2,782 Broadwings passed over the summit. The hawkwatch at Mount Watatic reported 3,874 Broadwings in September, with their peak count of 1,766 a day later on September 23. Paul Roberts, founder of the New England Hawk Watch, speculated that prevailing easterly winds this year forced the majority of Broad-winged Hawks to migrate farther west through central New Hampshire and Vermont, thus bypassing our region. Roberts noted, for example, that Putney Mountain, Vermont, recorded 12,045 Broadwings this year, exceeding last year's high of 11,728.

The hawkwatch at Wachusett Mountain also logged 134 Bald Eagles, which is 24 more than last year, and set new record counts for Cooper's Hawk (131), surpassing last year's total of 121, and Merlin (42), exceeding the previous high of 35 in 2014. Other raptor news included the first Rough-legged Hawk of the season, reported on Halloween from Plum Island, and eight Golden Eagles, noted from five locations.

The wet weather in September dampened migration, with observers at Manomet reporting conditions along the South Shore to be about as bad as they could be. The migration did, however, pick up during the last days of September and continued through October, during which strong winds from the south redirected migrants to the northeast. This phenomenon of reverse migration was especially notable on Cape Cod with many reports of vireo and warbler species that would normally have been long gone from our region.

.png?ver=2019-01-27-194840-130)

Figure 2. A Fatpoll! This Blackpoll Warbler was banded (#2160–46794) on September 20, 1999 weighing 11.5g. It was last recaptured weighing 17.3g on October 6, 1999 with a banding comment, "feels pudgy!" Photograph by Manomet Staff.

Fall migration usually offers more surprises than that of the spring. Rarities for the period this year included two reports of Say's Phoebe, one from Cuttyhunk Island and another in Barre that was present for two days. A report of a Bell's Vireo from Fort Hill in Eastham is no longer such a surprise. One wonders if this is the same individual that was present at this location on October 30–December 12, 2015, and October 24–27, 2016. Other rarities included six Western Kingbirds, a Lark Bunting in Provincetown, and a Summer Tanager in Belmont.

Since the fall of 1999, Ron Pittaway of the Ontario Field Ornithologists has prepared an annual forecast for winter finch distribution in the Northeast. The forecast is based on the relative abundance of seed crops in their breeding range, the Canadian boreal forest. Northern finches move south—or sometimes east or west—in late fall when there is a shortage of seeds. Some winters, they don't show up here in Massachusetts at all, while other years there are so many that they can empty your feeder in only a day or two. Pittaway predicted a major invasion of northern irruptive species this year, and so far he's been right. We have already seen large numbers of Red-breasted Nuthatches and Purple Finches; Pine Siskins arrived from mid-October; and Common Redpolls and Evening Grosbeaks started to appear in small numbers at the end of October.

It was a good migration for several species with exceptional numbers reported for Northern Flicker, Yellow-bellied Sapsucker, Eastern Phoebe, both species of kinglet, and White-throated and White-crowned sparrows. The Brown Creeper is a species that eludes many birders and hence may appear uncommon, but banding data suggest otherwise; in October alone the Plum Island banding station banded 64 Brown Creepers and Manomet banded 58. Sparrow migration reaches its peak in October. Among the highlights were 35+ Clay-colored Sparrows, 30+ Vesper Sparrows, seven Lark Sparrows, and more than 15 reports of Nelson's Sparrows.

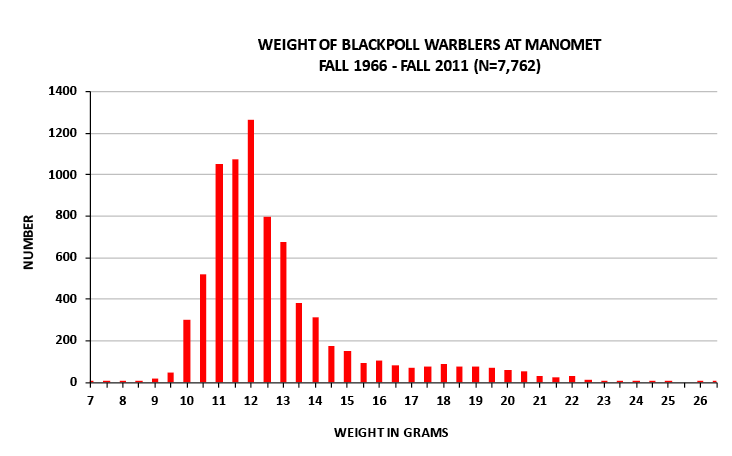

Migrating songbirds prepare for international flights by putting on large amounts of fat. That's especially true in the fall for birds like Blackpoll Warblers, which fly nonstop over the Atlantic Ocean to reach destinations in northeastern South America. By gorging on insects and fruit they are capable of more than doubling their weight—in the case of the Blackpoll, from just under 10g to over 20g. Experienced banders, like Trevor Lloyd-Evans of Manomet, can tell by handling the birds if they have enough fat to migrate. An example of a "fatpoll" warbler, weighing 17.3g, is shown in Figure 2. The heaviest Blackpoll recorded at Manomet in the last 50+ years was a bird weighing 26.7g on September 18, 1984. A distribution of Blackpoll Warbler weights, all banded in the fall at Manomet, is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Weight distribution of fall Blackpoll Warblers caught at Manomet, 1996–2011. Data from Trevor Lloyd-Evans, Manomet.

There were 35 different species of warbler noted during the period. The highlight was the second state record of Painted Redstart, photographed on Cuttyhunk Island on October 14. The only other record was 71 years ago at Marblehead Neck, October 18–19, 1947. Despite an intensive search, the bird could not be relocated. Other exceptional reports included a Black-throated Gray Warbler on Gooseberry Neck, Westport, a Prothonotary Warbler in Ipswich, present for over two weeks, and a Yellow-throated Warbler on Cape Ann. Also good for the period were a Golden-winged Warbler at Rockport, more than 50 Orange-crowned Warblers, and more than 35 Connecticut Warblers. It was a good breeding year for warblers that nest in the boreal forest to our north. The numbers of Cape May and Tennessee warblers this year exceeded those of last year and Blackpoll Warbler numbers were off the chart; 302 were banded at Manomet alone this fall.

R. Stymeist

References

- Maley, J. M., & R. T. Brumfield, 2013. Mitochondrial and next-generation sequence data used to infer phylogenetic relationships and species limits in the Clapper/King Rail complex. The Condor, 115 (2), 316–329.

- Kamm, M., J. Walsh, J. Galluzzo, and W. Petersen, 2013. The Massachusetts Breeding Bird Atlas 2. (J. Walsh and W. Petersen, Eds.)