David McLain

Call me Elizur. What do you think of when someone mentions the City of Holyoke? Paper mills, canals, the massive hydroelectric dam and fish lift, the mall, the old ski area and amusement park, ethnic diversity, and Nick’s Nest hot dogs come to mind. Crime, of course. Mount Holyoke College? Nope, that’s in South Hadley, but it does have Holyoke Community College. You might be surprised to know Holyoke is the birthplace of volleyball and home of the Volleyball Hall of Fame. It should also be the rightful birthplace of basketball, according to my friend, the late Clara Gabler, whose father, George, introduced a certain James Naismith to a game of throwing a ball into a peach basket at the Holyoke YMCA six years before Naismith honed the sport (Wheeler 1986). Birds? Probably not. Yet on spring migration counts, I can routinely tally over 100 species, sometimes in the 120s if the timing and weather are favorable.

Holyoke has a rich history of planning and development (Connecticut Valley Historical Society 1881, Wikipedia 2021). First explored by Elizur Holyoke in the 1650s, the settlement of “Ireland Parrish” would take nearly 200 years to become the township of Holyoke in 1850. The town chose its name from the Mount Holyoke Range, which Elizur had named after himself during his 1660 survey of the northern boundary of Springfield, what is now South Hadley. Rolland Thomas flanked Elizur on the west side of the river—the future Holyoke—naming that range Mount Thomas. Elizur’s 1653 survey on the west side resulted in the establishment of Northampton.

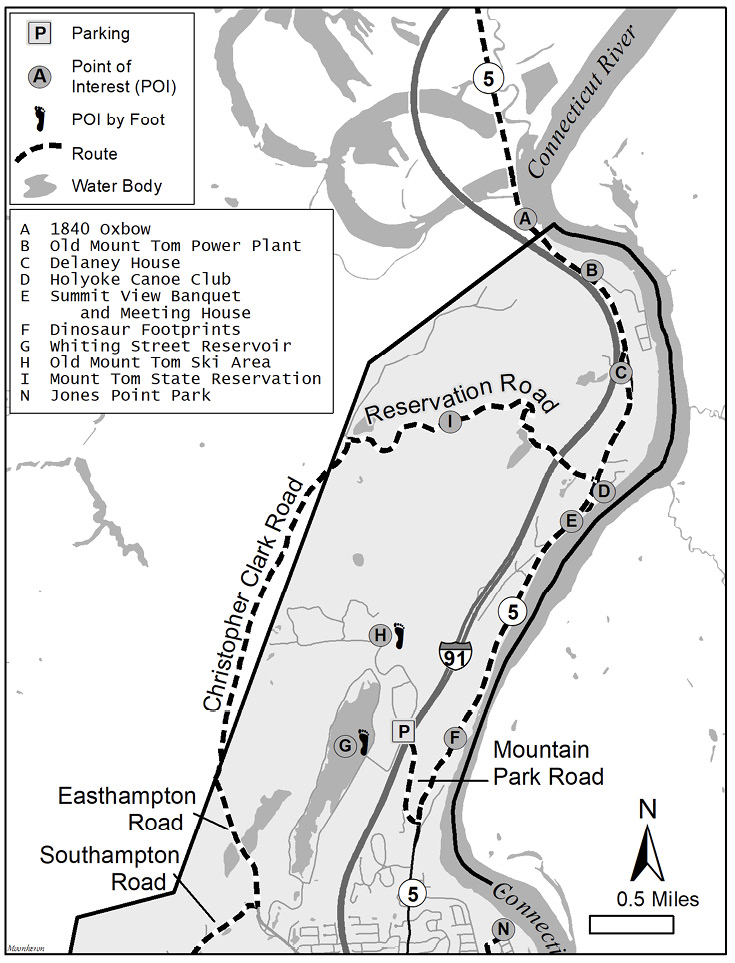

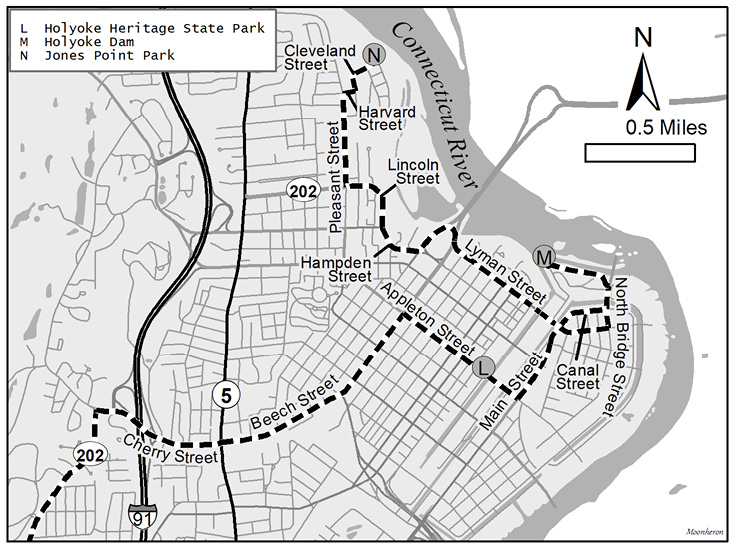

Figure 1. Northern Holyoke Overview Map.

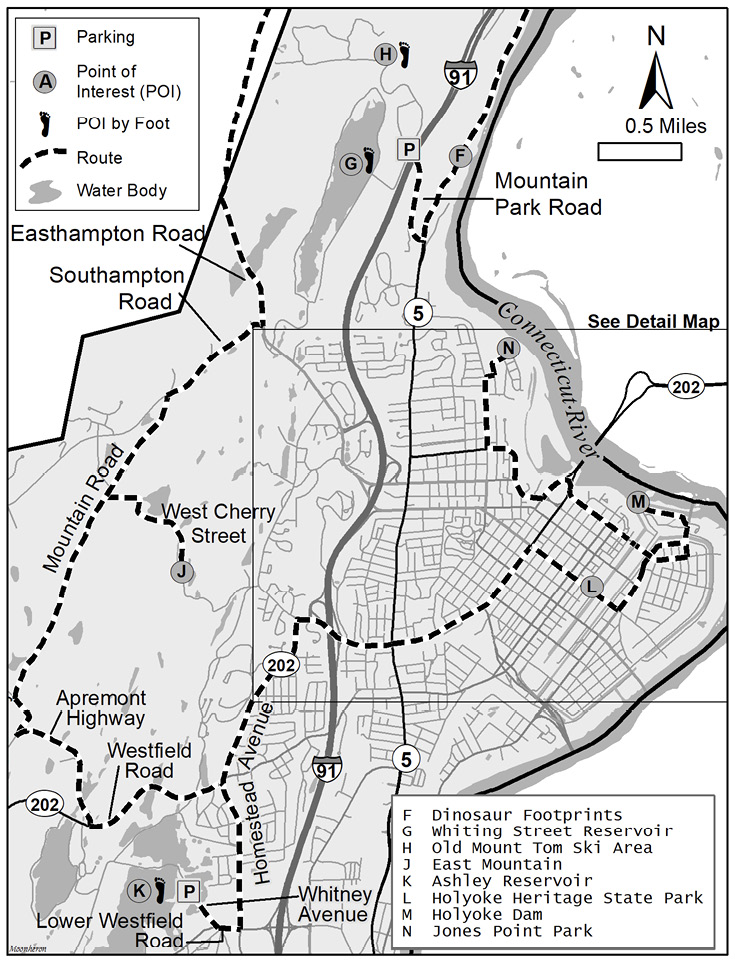

Figure 2. Southern Holyoke Overview Map.

The grid pattern of the downtown area and the flats were designed around the construction of a hydroelectric dam at Hadley Falls and the three levels of canals that supplied power to the numerous paper mills. Holyoke once supplied 80% of the country’s writing paper. City planning provided residential areas in the highlands and designated the village of Rock Valley (West Holyoke) for light development only. The northern extension of the city, known as Smith’s Ferry, was annexed from Northampton in 1909 after flooding at the Oxbow prevented Northampton firefighters from reaching the Canoe Club while it burned to the ground. Three reservoirs supplied ample drinking water, which they fluoridated. My South Hadley dentist could always tell the kids from Holyoke by their lack of cavities.

For an industrial city, the oddly shaped Holyoke landscape has a diverse array of productive habitats. Geographically, the 23-square-mile city is bordered by the mighty Connecticut River along its entire eastern edge. The expansive spillway below the dam has rapids flowing over boulders and ancient sedimentary rock. The current is also swift at the Dinosaur Footprints, while the rest of the river slowly meanders around long bends. Most of Holyoke’s stretch has some degree of riparian forest with silver maple and cottonwood, which makes it “snow” in May.

.jpg?ver=oz1rsCnrdbk5KSKIOG9_Qw%3d%3d)

View from the crest of the Mount Tom Quarry with Mount Holyoke peaks in the background. Amphibians breed in the pools below. Photo by David McLain.

The Mount Tom Range and East Mountain along the Metacomet Ridge compose most of the city’s western half. At an elevation up to 1200 feet, Mount Tom towers above the surrounding valley, providing exposed basalt cliffs, traprock slopes, and scrub oak-blueberry-huckleberry mesa. Both ranges abut reservoirs and their associated watershed land, forming a sizable, forested greenway from north to south, broken only by a few roads. Large swaths of oak-hickory-birch-ash forest are supplemented with patches of pine and hemlock, red maple swamps, and mixed woods. The two reservoirs provide open lake and pond habitat; Ashley Reservoir also has adjacent marshes. Two golf courses on the range provide open space with small ponds.

Agricultural habitats are scarce in Holyoke. A 25-acre working demonstration farm along the Connecticut River in the Ingleside neighborhood is about all that is left, along with an orchard on Homestead Avenue. A larger farm and productive birding spot in Smith’s Ferry was recently converted to a solar farm after one of the dirtiest coal power plants in New England shut down. Today, the city is nearly carbon neutral. The downtown urban area has a plethora of chimneys, flat-topped buildings, canals, and even some trees for urban wildlife.

As a Holyoke native, I have wandered most of the city for half a century—hiking, paddling, sledding, skiing, and fishing. I even have had birdies on both golf courses and eagles at both reservoirs, though now I use glass instead of irons. Since the mid-1980s, I have covered part of Holyoke for the Northampton circle of the Christmas Bird Count (CBC), and I cover the entire city for the Allen Bird Club (ABC) annual spring migration count, a 24-hour tally of species and their numbers.

Holyoke is underbirded. The city has 16 eBird hotspots: two yellow, three green, eleven blue, with the warmer the color, the more species reported—red and orange being highest—and a tad over 1400 combined checklists submitted, which is a mere fraction of major hotspots elsewhere in the Pioneer Valley. Many birders poach Holyoke birds from the South Hadley side of the dam, and a popular birding spot on Mount Tom is actually in Easthampton. Several veteran birders have spent time in Holyoke prior to eBird’s existence, and even my own sightings are lacking in the database, but some of the paucity of records may be from people’s perception of the city and unfamiliarity with its natural riches. All that may change as birders discover the bounty that can be found in the Paper City.

Birding Holyoke can be done in various ways, depending on the season and your time and goals. On my ABC count in May, I try to maximize the number of species while counting individuals in representative sections of each area. While much of the city can be covered by car and on foot in a grueling 24-hour period, alternately you can spend an entire day hiking on Mount Tom or at Ashley Reservoir. Or you can head to the dam for a stationary vigil or take several quick peeks along the big river. A birder can drive to various locations for several short stops and compile a decent list in a single morning. However, hitting the 100-species mark in spring usually requires spending quality time at key sites. Keep in mind, you must be everywhere at dawn! Fall and winter are more forgiving with bird activity spread more evenly throughout the day, and not all sites are productive.

Whatever your pace and mode of transportation, this guide will lead you through numerous birding spots as you retrace Elizur’s 1653 expedition, albeit over a much-changed landscape. It covers a large geographical area, so tailor your birding trip to your interests and schedule. The suggested route visits the sites progressively from north to south, as shown in the two overview maps, northern Holyoke (Figure 1) and southern Holyoke (Figure 2). Or you can skip ahead to hit productive areas earlier in the morning. A more relaxing strategy on a short time budget would be to visit different sites on successive days. Parts of the river can be birded from your dugout canoe via a few access points:

- Oxbow State Boat Ramp, 978 Mt. Tom Road, Easthampton.

- Brunelle’s Marina, 1 Alvord Street, South Hadley.

- South Hadley Canal Park, 99 W Summit Street, South Hadley.

- South Hadley Dam Put-in, 128 Syrek Street, Chicopee.

- Jones Ferry State Ramp, 11 Jones Ferry Road, Holyoke.

See https://massachusettspaddler.com/connecticut-river-access.

You can reach Holyoke via Interstate 91 (I-91) from the north by taking new Exit 23 and heading south on Route 5, or from the south by taking I-91 to new Exits 10, 11, 12, 14, or 15.

Connecticut River North

Directions:

To begin this birding guide’s suggested route, no matter which direction you come from, take I-91 to Exit 23, and drive south along Route 5 into Holyoke, with several river views and short stops along the way.

Target birds:

Common Goldeneye (winter) and other waterfowl, eagles, swallows, orioles, migrant warblers, Blue-gray Gnatcatcher.

Head south from Exit 23 on Route 5 for 2 miles to the first pulloff on the left at the city line (A). With the caveat that crossing the railroad tracks on foot is a no-no, you can view the river near the mouth of the 1840 Oxbow where Bald Eagles may be found. Downstream is Holyoke’s reach of the big river.

Next, drive south for 0.6 mile, and take a left into the old power plant grounds (B). The Mount Tom Power Plant tower, an iconic scar on Holyoke’s landscape, was toppled recently, and the future of that property is uncertain. Some shrubby habitat at the entrance makes good birding. A solar farm has usurped a productive cropland and brown field on the south end of the property, but shrubs and a small woodlot are birdy.

Return to Route 5, and continue south for 0.6 mile. Turn right onto Smith’s Ferry Road. Look for the entrance road to the Holyoke Country Club approximately 700 feet before you get to the Delaney House (C). Country Club Road has a few spots to check, including a swamp near the parking lot. Also, scan the golf course and mountain.

Drive south on Smith’s Ferry Road to return to Route 5. In 0.7 mile, turn left onto Old Ferry Road, and head north to the Holyoke Canoe Club (D) for another look at the river. (Brunelle’s Marina on the east side of the river in South Hadley has a better view of the Holyoke side, as fellow CBC counters over there tell me what I’ve missed.)

Drive south on Old Ferry Road to return to Route 5, and in 0.2 mile pull into the Summit View Banquet and Meeting House (E) on the right. Park in the back lot. A walkway leads north to Jericho, a social services organization; the pond often produces a Green Heron. Take several looks in the open wooded area to catch a good mixed warbler flock here when the timing is right.

The next stop farther south is the Dinosaur Footprints (F) at a turnout on the left, 1.5 miles past Summit View. The mud from the ancient riverbank hardened to sandstone, revealing the intact trails of the first scientifically described tracks of early dinosaurs (Trustees 2021). You will have to write in the proto-birds you find from 200 million years ago and hope for a sympathetic reviewer. While your inner paleontologist is kicking in, modern dinosaurs, such as Blue-gray Gnatcatcher, American Redstart, and Baltimore Oriole, will be flying and singing around you in the open riparian forest in season. A stream at the end of the footprints viewing area may harbor a Louisiana Waterthrush. A trail leads down to the river where you will see a spectacular display of varved sandstone layers just beyond the sign telling you not to cross the railroad tracks. Scanning the river, you will find large flocks of migrating swallows in March and April. The flocks move up the section of rapids and then drop back downstream to start over. In winter, the rapids are a reliable place for Common Goldeneye, with an occasional Barrow’s Goldeneye. With snow, the parking area is usually closed. I park along the entrance road to Whiting Street Reservoir and the old Mount Tom Ski Area and then cut through the woods to the ruins of the old entrance road and walk down Route 5 to the Footprints.

Whiting Street Reservoir and Mount Tom Ski Area

Directions:

From the Dinosaur Footprints, continue south on Route 5 for 0.6 mile to the next right on Mt. Park Road. Park either after or before the I-91 overpass, and walk west to the gates. The gate on the left leads to the Whiting Street Reservoir (G); the one on the right leads to the old Mount Tom Ski Area (H).

Target birds:

Ring-necked Duck, Ruddy Duck, Hooded Merganser, American Coot, Common Raven, Eastern Whip-poor-will, American Woodcock, Wild Turkey, Peregrine Falcon, Eastern Bluebird, Field Sparrow, Eastern Towhee, Indigo Bunting, Prairie Warbler, Blue-winged Warbler.

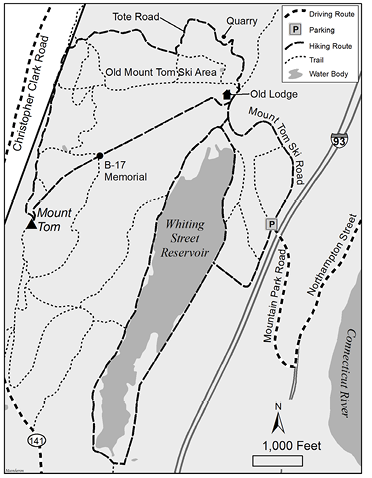

Figure 3. Whiting Street Reservoir and old Mount Tom Ski Area.

Several hiking options are available from here (see Figure 3): a loop around the reservoir, a climb up the old ski slopes, an alternate route to Mount Tom Peak, a visit to the abandoned quarry, a side trip to a red cedar stand, or a connection to the trails at the Mount Tom State Reservation. Except for the road around the reservoir, most of the other routes will give you a good hill workout.

Take the gate to the left to head to the reservoir. The watershed forest along the way is a mix of pine, maple, and oak frequented by Brown Creeper, Red-breasted Nuthatch, and Winter Wren. Check the stand of Norway Spruce before the pump house for Golden-crowned Kinglet, winter finches, and boreal warblers. Climb the steep stairway to the pump house to be rewarded with a scenic view of the long north-south reservoir against the backdrop of Mount Tom. Here you have a choice of taking the three-mile loop around the reservoir or heading north to a trail to the old ski area.

Waterfowl most often congregate toward the north end. The south end is not visible from the pump house and has limited views from the road, but sometimes has mergansers or even a Gadwall or scaup. I usually head north where mixed flocks of ducks and geese are easy to scan. A spotting scope is helpful, but cumbersome if you are planning a long hike beyond the reservoir. My Nikon Coolpix P900 acts as a suitable lightweight scope for identification. In late fall and early spring, Ring-necked Ducks can number over 100 and are often joined by American Coot, Ruddy Duck, Hooded Merganser, Lesser Scaup, and Greater Scaup. American Wigeon will follow the coots, plotting to steal their food after they surface from a dive.

If you have not killed your time budget just watching the ducks, continue around the north end of the reservoir to the second bend—about a mile from the pump house—to a trail on the right. The trail comes out on Mount Tom Ski Road. Winter Wren often skulks around the rocky slope and cascade here. Immediately to the left, a gated road leads steadily up to the WHYN radio tower at Mount Tom Peak, passing by the Mount Tom B-17 Memorial where a WWII plane carrying 25 servicemen tragically crashed on their way home. Before taking this road up the mountain, keep going a short way to the base of the ski slopes, listening and scanning for birds, then return to the gated access road to the summit. Worm-eating Warblers and an occasional Cerulean Warbler, along with Common Ravens, raptors, Great Crested Flycatchers, breeding Dark-eyed Juncos, tinkling ground crickets, crackling grasshoppers, leeward butterflies, and a spectacular view make the arduous hike worthwhile.

For a geologically interesting loop, continue north from the radio tower along the Metacomet-Monadnock (M-M) Trail for about a half mile to another radio tower and trail to the top of the Upper T slope of the former ski area for a shorter direct route down to the lodge, or continue a short way along the M-M Trail to the next tower and the top of the main spoke of ski slopes. If you find yourself here at dusk, Eastern Whip-poor-wills and American Woodcocks will take your mind off how far from the car you are. I hope you planned the trip with a fully charged phone, a snack, and plenty of water. But it is all downhill from here, almost.

The Upper and Lower T slopes provide an excellent example of old-field habitat. The grassy slopes now have young pines and scattered shrubs that favor Field Sparrow, Prairie Warbler, Eastern Towhee, Indigo Bunting, and Wild Turkey. I have found Northern Shrike multiple times in winter—once on a CBC—making the climb up from the base justify the many times I have left shrike-less.

At the trail by the second tower, two chairlift dismounts were the gateway to the Big Tom, Waterfall, and Vista ski slopes, with the Sidewinder stemming off the Vista. Head north along the top of the slopes to Tote Road. The Tote Road Trail veers off to connect with other Reservation trails or eventually back to the old base lodge. Continue on the actual Tote Road, where rebel skiers from my youth would break the rules and wreck their skis on this rocky, unofficial slope trail. As you descend, listen for the sweet-sweet, sweat-sweat, choo-choo-choo of Northern Waterthrush at Mountain Park Reservoir, a water supply for snowmaking machines, or look for a Hermit Thrush surviving on winterberry in winter. Just beyond the pond, you will come to the top of the Boulevard slope before viewing the quarry.

The quarry, abandoned since 2012, has been the center of controversy recently because a Holyoke development company seeks to fill in the huge crater with construction material over a 20-year period (Johnson 2021). The Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), however, has stakes in the property from a 2002 purchase of the Mount Tom Ski Area. To some Holyokers, the quarry is a scar on the landscape, with some homeowners rallying around slogans such as “Mount Tom: I don’t dig it.” To Peregrine Falcons, it is an occasional nesting and roosting site. To hikers, it is a scary, yet geologically interesting spectacle.

Tote Road has two views of the quarry from above for scanning its cliffs. After the second overlook, the trail meets the Boulevard slope with old-field habitat and Blue-winged Warblers amid shrubby areas in spring. A sumac stand may yield bluebirds, robins, and other frugivores in fall and winter, while spruce plantings add a boreal element to the landscape. Bluebirds, hard to find in Holyoke, sometimes nest around the base of the slopes. The old ski lodge and many of the outbuildings have been demolished, and the future of the site, formerly owned by Holyoke Boys & Girls Club, is uncertain.

When you get to the former ski lodge, you have two choices: you can return to your car via the Mount Tom Ski Road, or you can continue hiking. For the red cedar stand and Knox, Bray Valley, and Bray Loop trails, refer to the Trustees’ trail map of Little Tom: https://thetrustees.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Little-Tom-Trail-Map.pdf. Head north to view the base of the quarry before looking for the Knox Trail to the east. The dotted spur off the Knox Trail on the Trustees’ map leads to a red cedar stand near a Route 91 rest area. Be optimistic for the namesake Cedar Waxwing, along with thrushes and possible Hooded Warbler. A small pond downslope may attract an occasional Belted Kingfisher.

The Knox Trail connects to Bray Loop Trail where you can take a right along a stream to a swamp before looping back from Lake Bray; or go left to the Bray Valley Trail that will bring you back to the quarry and ski lodge. From the lodge, continue down the entrance road past the Mountain Park Theater lawn. The shrubby wet thicket down the hill is productive before you head up the last hill to your car.

Mount Tom State Reservation

Directions:

To get to Mount Tom State Reservation from the Whiting Street Reservoir, turn left onto Route 5, then in 2.5 miles turn left onto Reservation Road. From I-91, take Exit 23 to Route 5, go south for 3.4 miles, then turn right onto Reservation Road. Alternatively, from the west, take Route 141 to Christopher Clark Road (see Figure 1).

Target birds:

Peregrine Falcon, Common Raven, Worm-eating Warbler, Prairie Warbler, Winter Wren, Eastern Whip-poor-will, Golden-crowned Kinglet, Scarlet Tanager.

Managed by the DCR, Mount Tom State Reservation covers 2,000 acres of the Mount Tom Range. The reservation charges a $5.00 fee between Memorial Day and Labor Day. Twenty-two miles of trails would take days to cover, and some are steep, so shorter loop trails and stops along the road are ideal for birding. Here is the link for the DCR’s reservation map: https://www.mass.gov/doc/mt-tom-state-reservation-trail-map/download.

From the main entrance on Reservation Road, drive down the hill to the parking lot for Lake Bray on the left. The Bray Loop Trail is relatively flat and provides looks at the pond as well as a small stream and marshy swamp, a good place to pick up Pileated Woodpecker and Eastern Wood-Pewee, with hopes for Olive-sided Flycatcher. You can also access this loop from the Mount Tom Ski Area (see Figure 3 and the Little Tom map: https://thetrustees.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Little-Tom-Trail-Map.pdf). With time and energy, add the Lost Boulder Trail to the loop for a traverse through a unique hickory forest. On the east side of the road from Lake Bray, Bray Brook Marsh is an extensive shrub and sedge marsh with abundant birds, including Hooded Merganser, Alder and Willow flycatchers, and Chestnut-sided Warbler.

Continue on Reservation Road where several pulloffs and trailheads provide quick stop-and-listen birding or longer trail excursions. Louisiana Waterthrushes sing their warbled song along Cascade Brook. Blackburnian Warbler, Black-throated Green Warbler, Ovenbird, and Scarlet Tanager are common throughout the extensive forest. Watch for Swainson’s Thrush on the road in May.

At the stone house Visitor Center and Pavilion, scan the mowed lawn for field and edge species before taking a relatively flat loop from Keystone Trail to Quarry Trail on the south side with a few small, wooded ponds, or the Monadnock-Metacomet (M-M) Trail on the north side up to the lookout tower at Goat Peak. The tower, which can alternatively be reached on foot from the closed section of Christopher Clark Road, is a great place to watch for hawks and warblers in spring and fall. I have found Red Crossbill on this trek in winter. Tom Gagnon has a long-term tally of Common Nighthawks from his tower vigils. If the tower is crowded, try an opening just downslope, or climb the M-M Trail from the Pavilion to Whiting Peak. With time and energy and plenty of water, continue along the M-M Trail or the closed road to the vista overlook at Mt. Nonotuck. A short trail from there will take you to see the ruins of the Eyrie House, a once-thriving hotel that burned in 1901 (Atlas Obscura 2021). You might see birds too.

Back at the Visitor Center, take Christopher Clark Road to Route 141, stopping at the scenic overlooks along the way and birding along the road. A microburst windstorm swept through on October 8, 2014, toppling and topping a swath of trees. Described by some as a devastating destruction at the time, the storm damage was merely a disturbance that reset the forest to early succession. The area now supports a wide variety of birds not common elsewhere on the Mount Tom Range, including Winter Wren, Eastern Towhee, and Prairie Warbler. The slope between the road and the peak is where birders come to see or hear Worm-eating Warbler. Come back by foot at dusk from the Route 141 entrance to hear the incessant calls of Eastern Whip-poor-wills, another beneficiary of the microburst. Keep in mind that Christopher Clark Road is in Easthampton if your birding is restricted to Holyoke. Birds at the peak, such as Peregrine Falcon and Common Raven, are in Holyoke.

Before Memorial Day, the entrance gates to the reservation are usually not open until 8:00 am and close at 6:00 pm, so plan accordingly. When the gates are open, you can hike to the Mount Tom Peak and Whiting Peak by leaving one car at the Route 141 entrance and another at the Pavilion parking lot. Or take an up-and-back hike to Mount Tom Peak from the trailhead opposite Mt. Joe To Go drive-thru coffee shack on Route 141, or to Whiting Peak from the Pavilion parking lot. Another trail on the west side of Route 141 leads through deciduous forest and near a cattail marsh.

In winter, the best birding in the reservation is around Lake Bray and trails through hemlock forest, such as Kay Bee Trail, T. Bagg Trail, the parking lot at the upper end of the Keystone Trail, and the closed road to Goat Peak. My Christmas Bird Count area usually has the high count of Golden-crowned Kinglets and Brown Creepers. Just as nuthatches associate with chickadees, a creeper or two are sure to be amid a flock of hovering kinglets. Their high-pitched two-note call will help tip you off to their presence, as will a glimpse of a bird flying down from the top of a tree trunk to the base of another where it begins its creeping ascent in search of insects. Avoid areas of extensive hardwoods in winter; I have walked for miles tallying only a single Hairy Woodpecker.

From Route 141, you have the option to head to East Mountain, Ashley Reservoir, or downtown to the dam.

East Mountain

Directions:

Exit the park via the western entrance on Christopher Clark Road. Turn Left onto Route 141 for 0.8 miles, then turn right onto Southampton Road. In 0.7 mile, turn left onto Mountain Road, and in another 0.7 mile turn left onto West Cherry Street.

Target Species:

Eastern Whip-poor-will, Sora, raptors, woodland warblers.

East Mountain is a continuation of the Mount Tom Range through West Holyoke, and the two are connected by the Metacomet-Monadnock (M-M) Trail. At 778 feet in elevation, its rise above the surrounding terrain is not as dramatic, but the mountain is no less extensive. The habitat is more uniform oak-hickory-ash woodland with scrub oak along the plateau. Basalt cliffs are visible but less dramatic than those of Mount Tom. An impoundment of Broad Brook with marshy bordering wetlands off West Cherry Street had been a prime birding area before development of a few houses cut off access.

MassWildlife, the Holyoke Conservation Commission, the Connecticut River Watershed Council, the cities of Easthampton and West Springfield, and other entities protect much of East Mountain (MassWildlife 2021). Pick up the New England National Scenic Trail, which includes the M-M Trail, at Route 141, where you can choose to hike short, medium, and long loops. Access to the middle section and a quicker route to the cliffs is from West Cherry Street. Access the southern end from Route 202 or Apremont Highway. Also, you can access trails on the west side of Holyoke Community College.

I prefer to start in the middle at the gate on West Cherry Street, but birding is good along the road from the pond to the gate and along the discontinued road beyond the gate. The pond has a marshy edge with Swamp Sparrow and Sora. Eastern Whip-poor-will breeds on the scrub oak cliffs and can be heard from below after dark. Wood warblers, vireos, thrushes, and tanagers are main targets in the forest here.

For a hike to the cliffs and some raptor-watching, look for a trail opposite the Holyoke Revolver Club before the gate. The trail is steep at first, then winds around for less than a mile to a scenic overlook of West Holyoke. Though not as good for hawks as Goat Peak, the cliffs give a view of the open sky away from the crowds of Mount Tom. Take the trail back the way you came. Or you can plan a longer loop to the south that will come out on the discontinued road.

Ashley Reservoir

Directions:

From West Cherry Street, take a left onto Mountain Road. In 1.3 miles, bear left onto Rock Valley Road, and in 0.25 mile turn left on Apremont Highway, which comes to a T at Route 202 (Westfield Road). Take a left onto Route 202, and in 0.9 mile turn right at the first light onto Homestead Avenue. Continue 0.9 mile to the next light, and turn right onto Lower Westfield Road. In 700 feet, turn right onto Whitney Avenue, and park in the lot after the Elks Lodge. You can hike the trails and either walk or bike the reservoir loop.

Target Species:

Migrant waterfowl, Osprey, Bald Eagle, Common Loon, Spotted and Least sandpipers, Yellow-bellied Flycatcher, warblers—Wilson’s, Mourning, Magnolia, Pine—and fluffy, downy goose chicks.

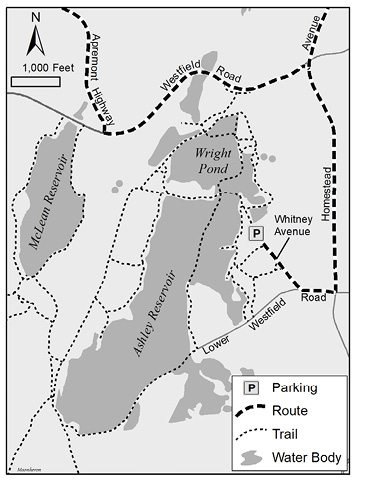

Figure 4. Ashley Reservoir.

Ashley Reservoir is a series of ponds with a perimeter road, crisscrossing causeways, and trails leading to East Mountain and McLean Reservoir. The surrounding forest is a mix of oak stands and pine plantations. The main ponds are clear, with submerged vegetation along shallow edges where you might find yourself fish watching for bass and pickerel more than birdwatching, especially if you have polarized sunglasses. Smaller ponds have floating and emergent vegetation, attracting dabbling ducks and marsh birds.

The road around the reservoir is 3.5 miles, and numerous trails can make the adventure much longer. I find that birding by bike around the road saves time and energy. The trails to East Mountain are rugged hilly ATV trails, so I lock my bike to a tree and hike them on foot.

From the parking lot, cross the gate and walk down the road to the reservoir. Before you reach the main ponds, a shrubby wetland on the left is full of swampy marsh birds. A small pond on the right may produce a Green Heron among dozens of turtles. Take the trail on the right just after the pond for a short walk into the woods for some warblers and a BMX course. Return and continue on to the main ponds where you will come to a four-way trail intersection. Take the causeway to the left.

The largest pond will be on your right, where diving ducks in spring and fall may include scaup, scoters, Ring-necked Duck, Ruddy Duck, or even a Long-tailed Duck or Bufflehead. Look for loons and grebes as well, or perhaps a Bonaparte’s Gull. Spotted, Solitary, and Least sandpipers may forage along the shore of the causeway, especially at the widened section.

When you reach the trees on the causeway, an open area on the left will help boost your species list with Killdeer, Least Flycatcher, or Savannah Sparrow in the weedy field and sandpit. I have had spring Yellow-bellied Flycatchers in this area and elsewhere at Ashley.

Continuing along the perimeter road, you will come to an intersection with another entrance gate on the left. A footpath across the intersection leads to views of two marshy ponds where you might find dabbling ducks, such as Blue-winged Teal, Northern Shoveler, and Wood Duck, along with herons, swallows, and Belted Kingfishers. You will get another look at the larger pond on the left as you continue around the perimeter road.

The southern end of Ashley Reservoir is a destination spot. Check the marshy shoreline in front of the pump house for shorebirds. The left side of the road parallels a railroad track where dense, shrubby habitat is productive for migrant warblers such as Wilson’s, Mourning, Canada, or even Connecticut. More thickets are around the bend toward the dam spillway and outlet stream where you can find Louisiana Waterthrush.

A trail on the left side of the road past the spillway leads to East Mountain and the M-M Trail. Turning right will lead to the north for a brief look at McLean Reservoir. From there, head west to see more of the East Mountain ridge, or loop back to the reservoir and bird your way back to the Elks Lodge.

Downtown Holyoke & Heritage State Park

Directions:

To Heritage State Park from Ashley Reservoir and the Elks Lodge, return to Lower Westfield Road. Turn left onto Homestead Avenue, driving for 2.0 miles straight through the lights at Westfield Road and past Holyoke Community College. At the T-intersection, turn right onto Cherry Street. When you cross Route 5 (Northampton Street), Cherry Street becomes Beech Street. In 1.1 miles, turn right onto Appleton Street. Heritage State Park is on the left in 0.4 mile.

Target birds:

Peregrine Falcon, Chimney Swift, Pine Grosbeak, city birds.

Figure 5. Holyoke Center detail.

Downtown Holyoke is an urban habitat with a surprising array of birdlife, and Holyoke Heritage State Park is a green oasis in this urban setting. Although eBird records show only a handful of species, not including the dam area, Greg Saulmon has amassed a list of over 80 species, including hawks, three falcons, herons, waterfowl, winter finches, and several warblers (Saulmon 2021). His blog makes an excellent guide to the downtown area, highlighted by Heritage State Park with its fruiting trees for Pine Grosbeaks; buildings for nesting Peregrine Falcon, American Kestrel, and Red-tailed Hawk; and canals for waterfowl, including Common Goldeneye. The power company drains the three-level canals annually for maintenance, which exposes mudflats for a plethora of waders and shorebirds. In 1985, Seth Kellogg reported an impressive list of plovers and sandpipers—listed on the dam’s eBird hotspot—which may have been associated with the draining of the canals. On October 25, 2012, a Barred Owl became a spectacle for passersby on the Holyoke Health Center. It was injured and was taken to rehab, but it is likely that many other owls pass through the city undetected.

Holyoke Dam

Directions:

From Heritage State Park, continue southeast on Appleton Street, and turn left in 0.2 mile onto Main Street, which becomes Canal Street at the traffic light. From Canal Street, turn left onto Route 116 in 0.3 mile, and take the second immediate left in about 600 feet at the entrance to the Robert E. Barrett Fishway at the dam.

When the fishway is closed, you can visit the Holyoke Dam from the South Hadley side of the Connecticut River. After the fishway, continue on Route 116 over the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Bridge to South Hadley, taking a déjà vu left onto Main Street, which becomes Canal Street. Park at the South Hadley Public Library lot or continue to the Canal Park.

Target birds:

Bald Eagle, Osprey, Common Merganser, Double-crested Cormorant, Great Blue Heron, Rough-winged Swallow, Bank Swallow, gulls, shorebirds, and rarities.

The Holyoke Gas & Electric Company operates the Barrett Fishway, an elevator for lifting anadromous fish, such as American shad, blue-backed herring, sea lamprey, and Atlantic salmon over the dam. A glass viewing area lets you watch the fish swim through a channel after getting a lift from the elevator. An outdoor platform lets you watch the elevator in action. It also gives you a great view of the dam and the spillway. However, the facility is open to the public only during the shad run in spring, and it was closed entirely in 2020 and 2021 due to pandemic restrictions. Check online for its status before planning a visit.

When the fishway is closed, proceed to the South Hadley side where you can access a viewing walkway near the library. That site also was closed during the pandemic but reopened in 2021. Farther along Canal Street, you will find a viewing platform at the Canal Park where you can see the river upstream from the dam. A spotting scope is helpful from the platform.

When the mighty Connecticut River is in flood stage, the current is awesome and violent below the dam, but birds are not always there to admire nature’s power. The best times are at lower stages when birds can perch on top of the dam or on a shelf below the dam wall, and on exposed rocks that create pools and eddies downstream. A treed island provides shelter for warblers and perches for eagles.

The spillway below the Holyoke Dam attracts a wide variety of birds. If you are hoping to find unusual species in Holyoke, the dam area is probably your best destination. Eventually, something rare will show up. The usual suspects of gulls, cormorants, herons, and mergansers often have rarities among them. Recent sightings include Black-legged Kittiwake, Iceland Gull, Bonaparte’s Gull, Great Cormorant, Long-tailed Duck, Brant, American Golden-Plover, Purple Sandpiper, Dunlin, Little Blue Heron, Glossy Ibis, and Black Vulture, with Red-throated Loon, Greater Scaup, and White-winged Scoter being spotted from the platform at the Canal Park upstream. In May, when Common Merganser is hard to find elsewhere, the dam is a reliable location. In 2019, a harbor seal with a troubled childhood found its way upriver to the dam (Kinney 2019).

Jones Point Park

Directions:

From either side of the dam, head back to North Bridge Street in Holyoke, and turn right on Canal Street. At the light, turn right onto Lyman Street. (If construction is still in progress, follow the detour to get back to Lyman Street.) At the end of Lyman Street, turn right onto Route 202, and quickly bear left on the partial roundabout. Turn right at the lights onto Hampden Street, and in 0.3 mile bear right at the top of the hill onto Lincoln Street. Continue around the bend, and in 0.3 mile turn right at the light onto Pleasant Street. In 0.4 mile, turn right onto Harvard Street, then turn left onto Cleveland Street. Park at the bottom of a dangerous skateboarding hill that left me with a scarred elbow. The parking lot is on the left at the end of Cleveland Road in 0.2 mile.

Jones Point Park comprises a small woodlot, tennis courts, and a Little League baseball field where I once hit three homers in one game and got thrown out at home trying for a fourth. My longest hit ball of the game was actually caught by a fly catcher. The woodlot upslope from the tennis courts has a trail through it that passes a small pond before coming back to the fields. You might pick up a Pileated Woodpecker and Wood Thrush in the woodlot, while scaring up a Green Heron from the pond.

Behind home plate, an opening in the fence leads to railroad tracks. To the left is a view of the Connecticut River at a place called High Rock, where some kids would play hookey. (I never did!) To the right is a series of trails that lead through open floodplain forest and clearings with a variety of birds, including Brown Thrasher, orioles, warblers, vireos, woodpeckers, and Bald Eagle. A large cattail marsh bordering Log Pond Cove may produce waterfowl, rails, and Marsh Wren. It looks like a good spot for Least Bittern. It is illegal to cross the railroad tracks, and this birdy location can be reached by launching a canoe or kayak at the South Hadley Canal Park and paddling across.

You now have taken a whirlwind tour of Holyoke with its rich diversity of birds, habitats, geological features, and historical artifacts. You could hike for days on its trails, so be prepared. In winter, I have found the most productive locales are along the Connecticut River and the Holyoke Dam, the coniferous areas of Mount Tom State Reservation, the reservoirs if there is open water, and the crabapples at Heritage State Park. Do not leave valuables in your car, which can be said for many places beyond Holyoke as well. Be sure to stop for lunch at Schermerhorn’s Seafood on Westfield Road for fish & chips—my bird count tradition—or Nick’s Nest on Route 5 for a hot dog and baked beans. Happy birding! Elizur.

References

- Atlas Obscura. 2021. Eyrie House Ruins. Holyoke Massachusetts. https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/eyrie-house-ruins. Accessed June 15, 2021.

- Connecticut Valley Historical Society. 1881. Elizur Holyoke. Papers and Proceedings of the Connecticut Valley Historical Society. Springfield, Massachusetts. 1:67. 1881.

- Johnson, P. 2021. Whose mountain is it?: State stakes claim on old Mount Tom quarry as owners seek bankruptcy protection. https://www.masslive.com/news/2021/04/whose-mountain-is-it-state-stakes-claim-on-old-mount-tom-quarry-as-owners-seek-bankruptcy-protection.html. Accessed June 15, 2021.

- Kinney, J. 2019. MassWildlife: Holyoke seal on Connecticut River was abandoned pup, rehabbed at Mystic Aquarium. https://www.masslive.com/news/2019/05/masswildlife-holyoke-seal-on-connecticut-river-was-abandoned-pup-rehabbed-at-mystic-aquarium.html. Accessed June 15, 2021.

- Massachusetts Paddler. 2021. Connecticut River Access Points. https://massachusettspaddler.com/connecticut-river-access. Accessed June 15, 2021.

- MassWildlife. 2021. Wildlife Management Areas important for rare species. https://www.mass.gov/service-details/wildlife-management-areas-important-for-rare-species. Accessed June 15, 2021.

- Saulmon, G. 2021. The Birds Downtown: Urban Birding, Holyoke Massachusetts + Beyond. http://birdsdowntown.com. Accessed June 15, 2021.

- The Trustees. 2021. Dinosaur Footprints. https://thetrustees.org/place/dinosaur-footprints/. Accessed June 15, 2021.

- The Trustees. 2020. Little Tom Trail Map. https://thetrustees.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Little-Tom-Trail-Map.pdf. Accessed June 21, 2021.

Wheeler, L. 1986. Sports World Specials; Basketball Tale. The New York Times, February 3, 1986, Section C, Page 2.

Wikipedia, 2021. Holyoke, Massachusetts. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holyoke,_Massachusetts. Accessed June 15, 2021.

David McLain is a wildlife biologist with degrees in the field from the University of Maine and University of Massachusetts. He has expert level experience with birds, freshwater mollusks, odonates, butterflies, orthopterans, fish, herps, and plants. He has worked in Puerto Rico on the Puerto Rican Parrot Recovery Project, Scotland and Iceland studying genetics of Atlantic Puffins, Panama on genetic differences between birds on the Pearl Islands versus the mainland, the Bahamas with hummingbirds, and numerous bird population studies in Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts. Dave lived and worked at Mass Audubon’s Arcadia Wildlife Sanctuary for 28 years, studying everything.