Nathaniel Sharp

The city of Burlington, Vermont, is bordered by Lake Champlain to the west and Vermont’s highest peak, Mount Mansfield, to the east. To the north lie the Champlain Islands and the Canadian border, and to the south, the rich agricultural lands of the Champlain Valley. The Burlington area and all birding locations described in this article are located on the traditional and unceded territory of the Abenaki Nation and People. As visitors on the land of the Abenaki People, all are encouraged to pay their respects to them, to the wisdom of their elders, and to their culture.

The city of Burlington, Vermont, is bordered by Lake Champlain to the west and Vermont’s highest peak, Mount Mansfield, to the east. To the north lie the Champlain Islands and the Canadian border, and to the south, the rich agricultural lands of the Champlain Valley. The Burlington area and all birding locations described in this article are located on the traditional and unceded territory of the Abenaki Nation and People. As visitors on the land of the Abenaki People, all are encouraged to pay their respects to them, to the wisdom of their elders, and to their culture.

A confluence of birds, wildlife, lands, and people, Burlington has a robust ornithological history spurred on by an active community of longtime local birders and an ever-present group of budding ornithologists and nature-minded students at the University of Vermont. Professors at the Rubenstein School of the Environment and Natural Resources, including but not limited to Allan Strong, Trish O’Kane, and Michael McDonald, are the driving force behind the birding energy that radiates from this campus; they often can be found with binoculars slung over their shoulders and a group of students in tow. As one of those students, I spent several years getting to know the best birding locations within walking, biking, and driving distance of the campus.

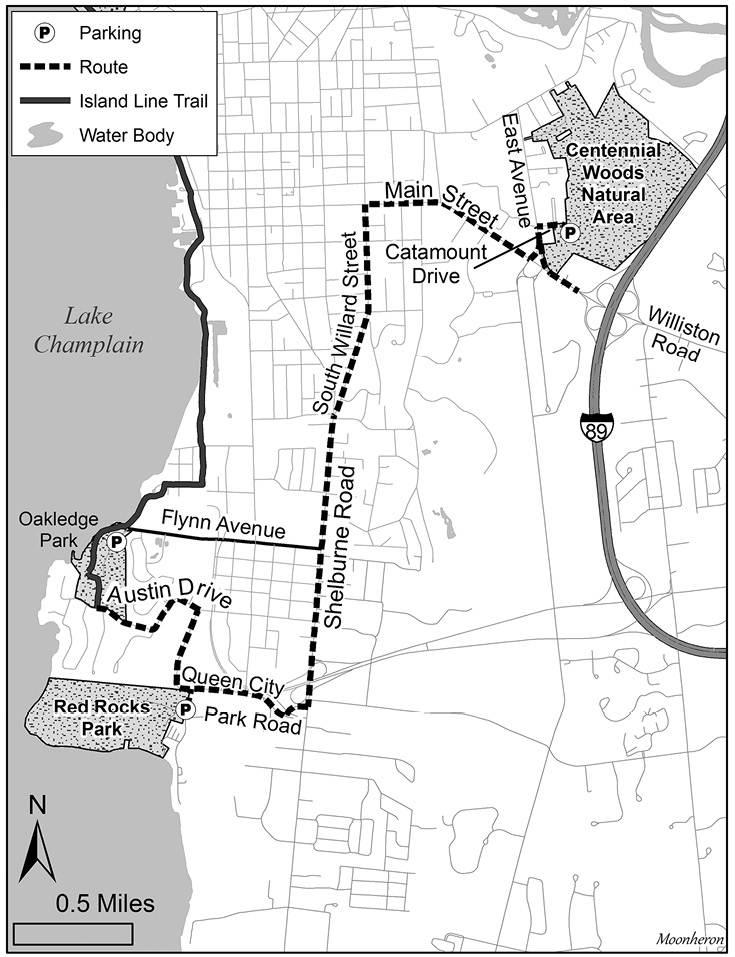

Many of the best birding spots in the Burlington area can be accessed along a biking and walking path along the shore of Lake Champlain called the Island Line Trail, so bring your bike or sturdy hiking shoes. Most of this article focuses on birding this trail by bike or on foot. I include several parking areas where drivers can access the bike trail and walk to the hotspots from there. Before exploring the Island Line Trail, I include two locations where you will drive: Centennial Woods Natural Area near the University of Vermont’s campus, then Red Rocks Park, along the shore of Lake Champlain.

Map of Burlington, Vermont.

Visitors to Burlington coming from the south will head North on Interstate 89 and take Exit 14W US-2/Williston Road (which turns into US-2/Main Street at East Avenue) into the city, where you will see the bustling sidewalks of the university campus. Upon cresting a slight hill, you will catch your first sight of the glimmering waters of Lake Champlain and the Adirondack Mountains towering in the distance.

Before you cruise past the main campus, it is worth checking out a hidden gem well known to students as one of the most diverse and easily accessible birding hotspots in Burlington—Centennial Woods Natural Area. Students and professors love this outdoor classroom due to its close proximity to campus.

After you exit the highway onto Williston Road, turn right in 0.2 mile onto East Avenue. Drive 0.2 mile and turn right at the stoplight onto Catamount Drive. (On some maps, this street is called Carrigan Drive.) In about 350 feet, there is a parking lot on the right directly across from Centennial Court on the left. Turn into this parking lot, and follow it to the end where you will find 4–5 parking spaces allotted to visitors of Centennial Woods. Across the street, the entrance to Centennial Woods Natural Area is marked with a sign.

Instead of entering Centennial Woods at this trailhead, walk south on Catamount Drive to one of a few scattered retention ponds, where Common Yellowthroats and Great Blue Herons hide in the reeds, and mixed flocks of sparrows and warblers sometimes gather in migration. Keeping your eyes to the skies, you may see the local Merlins, Peregrine Falcons, or Common Ravens flying overhead. Continue down the road to a large parking lot, and look for an entrance to the woods in the northwest corner of the lot; this will put you in the middle of a small clearing, where Lincoln’s Sparrows, Wilson’s Warblers, and Nashville Warblers, among others, can be found in the tangles of sumac and goldenrod. Continuing on the well-marked and easily navigable trails, you will enter the heart of the forest. Walk through stands of mature conifers and mixed hardwoods and check the hemlocks for the resident Barred Owls. Northern Saw-whet Owls also have been found roosting in these woods.

Camera trapping studies have revealed that fisher, gray fox, and many other mammals travel through or reside in this forest. Searching for animal tracks in the snow can be an engaging distraction during a slow birding day in winter. No matter which trail you take, you will eventually end up at some portion of Centennial Brook, a meandering trickle of water that broadens into a substantial wetland at certain places. Along the creek and the powerline corridor toward the north end of Centennial Woods, you may find any number of the 20-plus warbler species that have been reported here during spring and fall migration. The wastewater retention pond in the north end of the woods often hosts Mallards, American Black Ducks, and Wood Ducks, and for the last several years has been home to a nesting pair of Eastern Phoebes. Brown Creepers, Golden-crowned Kinglets, Black-capped Chickadees, and Tufted Titmice are a near-constant presence throughout the woods. During migration, the woods often host an interesting mix of warblers, vireos, and other migrants. Here are a couple of links to maps of Centennial Woods: <https://www.trailfinder.info/trails/trail/centennial-woods> and <https://www.alltrails.com/explore/trail/us/vermont/centennial-woods-loop--2?mobileMap=false&ref=sidebar-static-map&ref=sidebar-view-full-map>

The rest of the trip focuses on Lake Champlain, the main attraction for birders visiting Burlington. This unofficial Great Lake—120 miles long and 12 miles at its widest—has influenced the birds, the weather, and the people of the Champlain Valley for tens of thousands of years. Home to lake trout and—depending on whom you ask—prehistoric lake monsters, Lake Champlain has hundreds of birding locations along its shores. No matter where you find yourself birding along the lake, be sure to keep your eyes peeled for any sign of Champ, the fabled plesiosaur-like denizen of the deep.

The first stop at Lake Champlain is Red Rocks Park. Located in South Burlington, this park is the first stop on a birding journey along the Burlington coast of Lake Champlain that can be completed on foot, by bike, by car, or a combination. When you leave Centennial Woods, turn left onto East Avenue from Catamount Drive, then turn right onto Main Street. Follow Main Street for 0.8 mile, then turn left onto South Willard Street. In 0.9 mile, South Willard Street bears left and becomes Route US-7/Shelburne Road. Continue driving south for 1.3 miles, then turn right onto Queen City Park Road and right again to stay on Queen City Park Road. In 0.5 mile, take a left onto Central Avenue; the parking area for Red Rocks Park is on the right.

Red Rocks Park is named for its sheer cliffs composed of red Monkton quartzite. The cliffs are familiar to local thrill-seekers as prime (though off-limits) cliff-jumping spots, and to Common Ravens and Peregrine Falcons as excellent nesting and perching locations. To get to the overlooks, walk along the wide, well-maintained trails accessible from the roadside parking lot. It is best to arrive early during spring and summer because this location is popular with dog walkers. Here is the link to the trail map: <http://cms6.revize.com/revize/southburlington/document_center/RecsParks/RedRocksTrailMap.pdf>. Follow the trails through mixed hardwood forests and keep an eye and an ear out for warblers and vireos moving through the treetops. Spring migration, in particular, is a great time to bird Red Rocks Park. Year in, year out, I often find many of the first returning migrants of the season here, including Great Crested Flycatchers, Blackburnian Warblers, and Pine Warblers.

As you head toward the cliffs, you will enter one of the more interesting forest communities along Lake Champlain that comprises mainly northern white cedars, which become more stunted and gnarled as you approach the cliffs. If you need to take a break from straining your eyes to look for birds in the canopy, you can ward off warbler-neck by looking out across Lake Champlain and scanning the water for Buffleheads and Double-crested Cormorants, as well as Common Ravens dipping and diving on the air currents. A visit to the park in spring—ideal for seeking migrants—can also yield phenomenal numbers of ephemeral wildflowers, with lush carpets of trout lily, red and large white trilliums, dutchman’s breeches, and rock harlequin lining the sides of the trail.

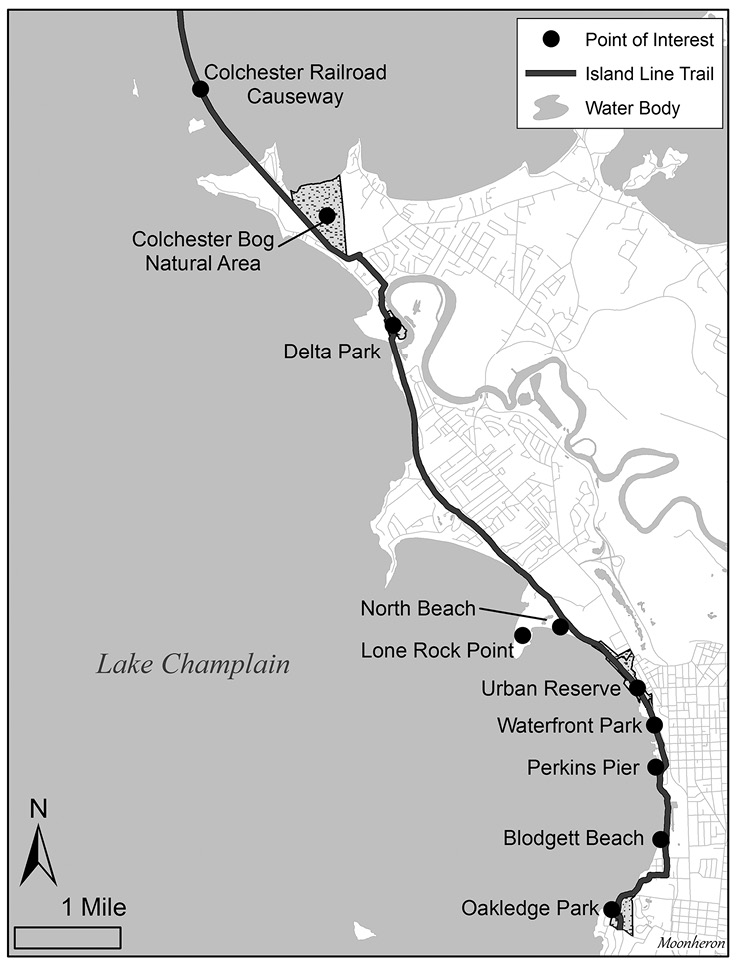

Map of Island Line Trail.

From Red Rocks Park, bike or walk north on Central Avenue for 0.1 mile, turn left onto Queen City Park Road, and travel 0.4 mile, past the headquarters of Burton Snowboards, to Austin Drive. Turn left and continue for 0.5 mile until you reach a bike path on your right. This is the Island Line Trail, a 14-mile rail trail with paved and crushed gravel surfaces suitable for bikers and walkers. It will take you north along Lake Champlain, through the bustling Burlington waterfront, all the way to the Colchester Railroad Causeway, a thin strip of land jutting more than 2.5 miles into the middle of the lake. <http://www.champlainbikeways.org/pdf/2017-Island-Line-Trail-Map.pdf> You can access a multitude of birding locations along the trail whether you are traveling by foot or on a bike, or you can drive to several places along the trail where you can park and get out to bird. Whether you bird Burlington in one day or several, the Island Trail Line is a useful route for birding the top spots in Burlington.

Bike or walk along the Island Line Trail for 0.5 mile to the first birding stop at Oakledge Park. If you are driving, parking is available for Oakledge Park on Flynn Avenue ($2/hour May-October). Oakledge Park features a mixture of open recreational fields and wooded areas, with another large lakeside patch of northern white cedars. The cedars often host mixed flocks of warblers and sparrows in spring and fall migration. As you travel through the park, stop to scan the lake from the Oakledge rocks or from Blanchard Beach, just north of the park. You may find a Red-breasted Merganser mixed in with Common Mergansers, or a Barrow’s Goldeneye hiding out in the flocks of Common Goldeneye that gather in fall and winter.

Colchester Railroad Causeway. All photographs by the author.

Walk or bike north on the rail trail for about 1.0 mile from Oakledge Park, past Blanchard Beach, to Blodgett Beach. Blodgett Beach is another great place to stop and scan the lake, where there are often flocks of gulls, geese, and ducks to pick through for prizes such as Iceland Gull, Bonaparte’s Gull, Cackling Goose, and Horned Grebe. If you put the beach at your back, you will notice the more industrial side of Burlington’s waterfront, where the train tracks and trainyard harken back to a time when lumber and other goods, rather than maple syrup and IPAs, were the major exports shipped up and down the lake.

Go 0.5 mile farther and you will arrive at Perkins Pier. The pier—as well as the surrounding area—is another great location to set up a scope and scan the lake and the breakwater. In summer, you may be lucky enough to spot a flyover Caspian Tern. In winter, peruse the groups of ducks and gulls on the lake and scan the concrete breakwater for a perched Snowy Owl or a flock of Snow Buntings. You can drive to Perkins Pier and park in the lot ($8 parking fee May-October). There is no parking at Blodgett Beach, so if you want to bird there, you’ll have to walk the mile roundtrip between Perkins Pier and Blodgett Beach.

From Perkins Pier, continue north on the bike path for 0.3 mile to Burlington’s Waterfront Park and breakwater. Drivers can park at the Pease Lot ($3/hour in summer, $2/hour in winter) at the western end of College Street. This is another place to scan the lake for ducks and gulls. My most memorable sighting at this location was when a stunning drake Harlequin Duck flew into the water just a few feet from where I stood waiting to catch a bus. Perhaps the most scenic part of Burlington, the waterfront boardwalk will provide you with stunning views across Lake Champlain to the Adirondacks. While you are birding your way through the waterfront, a stop at one of the numerous Creemee stands for Vermont’s famous maple soft-serve is a must, as is a brief birds-and-beers break from the patio of the incomparable Foam Brewers.

Caspian Tern.

As you bird your way north past Waterfront Park, the trail parallels the train tracks on your right and passes a skate park on your left. A little farther north and you will enter an area known as the Urban Reserve. A parking lot adjacent to the skate park between Penny Lane and Lake Street offers free parking year-round. This area, a piece of land that once was the heart of industry on the Burlington shoreline, hosts a dog park with open fields, many dense tangles of sumac and honeysuckle, and several spots for lake-watching. While completing an undergraduate project, I spent a lot of time documenting the birdlife of this seemingly insignificant spot and was delighted to find it full of migrants in spring. During spring migration, walking the bike path or the well-worn trails and sections of exposed concrete, I found mixed flocks of warblers, including Blackburnian, Wilson’s, and Nashville warblers, among others, as well as a Philadelphia Vireo on one occasion. The Urban Reserve is also a great spot for duck-watching in fall and winter, where you can view the lake and expect to find scoters, grebes, mergansers, and more.

Travel about 0.5 mile north on the Island Line Trail from the Urban Reserve, and you will arrive at the entrance to North Beach. To the right of the bike trail is the North Beach campground. North Beach is a bustling summer destination that is often a little quieter during spring and fall. It has several trails, lake vantage points, and a large pond that can host waterfowl and wading birds. North Beach is accessible by car. You can park in the lot at the end of Institute Road ($8 May-October).

Bohemian Waxwings feeding on crabapples.

Adjacent to North Beach is Rock Point Peninsula, 130 acres of conservation land owned by the Episcopal Church of Vermont that is open to the public. At the end of the peninsula is one of Vermont’s hidden gems, Lone Rock Point. Birding Lone Rock Point at any time of year is rewarding, though during mud season in early spring, some of the trails may be closed.

No matter how you arrive, all visitors are required to fill out a visitor pass online before visiting. The pass is free and you can download it from <https://www.rockpointvt.org/trails>. If you have parked at North Beach, it is a five-minute drive to a universal access parking lot off Rock Point Road, and you can pick up the trail to Lone Point Rock from there. To walk or bike to Rock Point, exit the Island Line Trail and walk through the campground, head up Institute Road, then turn left onto Rock Point Road.

Walking west on Rock Point Road, you will cross a bridge over the Island Line Trail. Follow the road to the left as it turns to gravel. Towering red pines and shagbark hickories signify a change in forest composition. You can find Brown Creepers and Pileated Woodpeckers scaling the shaggy bark of the hickories. Walk down the road past thick tangles of blackberry, sumac, planted yews, and fruiting trees and search for sparrows, vireos, and warblers, which are often found here in great numbers. After you walk past a private house and garden, you will see an interpretive sign kiosk with a trail map. Follow the trail to the left, which will take you through a forest of maples, oaks, and beech to an area known as the parade ground. This open field of goldenrod can be productive during fall migration, along with the surrounding edge habitat. Lincoln’s Sparrows, Tennessee Warblers, Ruffed Grouse, and Philadelphia Vireos are just a few highlights.

Champlain Thrust Fault and Lone Rock Beach.

Make your way across the field and back into the forest and follow the newly revamped trail south along the lakeshore to Lone Rock Point, which juts out into Lake Champlain. Geologically similar to Red Rocks Park, Lone Rock Point is the best place in Vermont to see the Champlain Thrust Fault. Stretching for almost 200 miles, this outcropping of Lower Cambrian Dunham dolostone that projects over the calcite-streaked shale of the Middle Ordovician Iberville Formation is nowhere more visible and stunning than at Lone Rock Point. This impressive geologic formation of older dolostone pushed up over newer shale is only made better by the Peregrine Falcons that nest nearby and often perch on the stunted, centuries-old white cedars hanging off the cliff face. Take one last look across the lake in search of loons and ducks, then return to North Beach, pick up the bike trail, and head to the next stop on this Burlington birding journey—Delta Park.

From the North Beach/Lone Rock Point area, Delta Park is 3.7 miles north along the Island Line Trail and, at mile 7, is the halfway point of the bike trail. If you have been walking the bike path, you may want to hop back in your car and drive to Delta Park, which is in Colchester, the town north of Burlington. The Department of Fish and Wildlife Access Area at Colchester Point is a large parking lot that can be accessed from Windemere Way. It is just north of Delta Park, so walk south along the bike path to explore the park. <https://www.wvpd.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Delta-Park-Trail-Map.pdf>

Biking or walking to Delta Park from North Beach, you will first see the park’s namesake delta from the bridge spanning the outflow of the Winooski River into Lake Champlain. Scan the lake from this vantage point to find Bald Eagles in just about any season. In summer, there are often Caspian and Common terns perched or flying over the water. Cross the bridge and travel over the forest floor on an elevated path that was installed so bikers and walkers could traverse the delta without impacting the movements of reptiles, amphibians, and mammals. Between spring and fall migration, more than 25 species of warblers have been found at Delta Park, often concentrated in the woods and tangles on either side of the path. Flooded sections along the path are magnets for Wood Ducks and Rusty Blackbirds.

Pine Warbler.

The elevated bike trail cuts through the woods for about 0.5 mile and ends at a suburban street, Windemere Way. Take a left down a small gravel road toward a secondary parking lot, where a trail leads to the lake. The wooded upland of Delta Park is a spectacular birding location; however, the wetlands, beaches, and shallow waters of the Delta Park lakeshore have racked up a total of 244 species—higher than any other location in Vermont. This represents more than 60% of the entire state bird list. During 2020, more than 200 species were reported to Vermont eBird from Delta Park.

Birding Delta Park is highly dependent on water levels, and because the wetland and delta system are located on a lake and do not experience tides, birding and access conditions can vary widely by season and year. In drought years when the lake levels are low, vast mudflats are exposed, and visitors can walk from the beach area all the way around the marsh to the base of the Island Line Trail bridge. Caspian and Common terns are frequently found perching on downed trees along the lakeshore. Green Herons, Great Egrets, Virginia Rails, and even Least Bitterns are often found in the marshes. Delta Park is a magnet for local rarities; a few notable records from the last few years include Nelson’s Sparrow, Yellow-headed Blackbird, Pomarine Jaeger, and Sabine’s Gull.

Red Knot.

During late summer and early fall, there is perhaps no place in Vermont where you can encounter a higher diversity of shorebirds. Semipalmated Sandpipers and Semipalmated Plovers are common, as are Pectoral Sandpipers and Least Sandpipers. Uncommon but regular shorebirds include Whimbrel, Stilt Sandpiper, Long-billed Dowitcher, Ruddy Turnstone, Sanderling, Red Knot, American Golden-Plover, Hudsonian Godwit, White-rumped Sandpiper, Baird’s Sandpiper, and Buff-breasted Sandpiper. With such an abundance of shorebirds, predators such as Peregrine Falcons and Merlins will frequently patrol the shores, and Northern Harrier, Short-eared Owl, and even Northern Goshawk hunt the marshes. When birding Delta Park during peak shorebird migration, it is best to wear waterproof footwear or sandals because you may have to do a little wading to access the shorebird flocks farther out on the delta. That being said, footing is steady and sure in most areas. There are few things better than standing barefoot in Lake Champlain scanning flocks of shorebirds on a sunny August day.

In winter, during years when the lake remains unfrozen, Delta Park can be a productive spot for winter ducks and gulls. Flocks of American Pipit, Horned Lark, and Snow Bunting are often found on the beach, along with the occasional Lapland Longspur. During any time of year, you will likely bump into the regulars—birders who frequent Delta Park and are happy to show you around if you are a birder new to the area.

There is one spot a little farther north that is a must-see for any birder visiting the Burlington area, and that is the Colchester Railroad Causeway. When you leave Delta Park and travel north, the Island Line Trail briefly follows the suburban streets of Windemere Way, Biscayne Heights, and Colchester Point Road before it resumes the paved, bikes-and-pedestrians-only path. You will continue through the Colchester Bog Natural Area, where you may find Rusty Blackbirds, Marsh Wrens, a nice mix of warblers and sparrows, and even some ripe blueberries in season. Two miles up the trail from Delta Park, you will arrive at the Colchester Railroad Causeway, a thin strip of rocks and concrete extending almost three miles out into Lake Champlain, where it abruptly ends at The Cut, a 200-foot gap in the causeway. To connect the Colchester end of the causeway with the end for Grand Isle County and the Champlain Islands, there is a seasonal bike ferry that runs between Memorial Day and Columbus Day. Officially, the Island Line Trail ends in South Hero.

Snowy Owl.

There is a parking lot located on Mills Point Road just south of its intersection with the Island Line Trail. Drivers can park here and walk along the bike path to the Colchester Causeway, the last stop along this birding route. If you want to walk through the Colchester Bog first, you can park at the southern tip of this area off of Colchester Point Road near the Airport Park Playground and ball fields and follow the road to pick up the Island Line trail.

The causeway is another location with variable lake levels, and vast mudflats will emerge from year to year and season to season. A scope is extremely helpful here, though not all birds will be distant. I was startled and thrilled to stumble upon a Northern Shrike hunting from the windblown treetops that line the causeway. You can often flush Wilson’s Snipe, Snow Bunting, and Savannah Sparrow from the rocks along the causeway.

The Colchester Causeway is a phenomenal location to find ducks, shorebirds, and gulls. In late fall and winter, flocks of Greater and Lesser scaups numbering in the thousands will often gather just off the causeway, and careful observers may be lucky enough to pick out a Tufted Duck among them. Scan groups of Ring-billed, Herring, and Great Black-backed gulls for Iceland, Glaucous, and Lesser Black-backed gulls. Common and Barrow’s goldeneye, Blue-winged and Green-winged teal, and Common, Hooded, and Red-breasted mergansers all can be found on the lake on either side of the causeway. During irruption years, multiple Snowy Owls have been found on the causeway and surrounding islands. Many of the same species of shorebirds found at Delta Park often can be found along the causeway’s mudflats.

Just about any time of year you visit the causeway, you will find a diverse assemblage of birds. Perhaps my favorite time of year to visit is the harshest. Trudging out to the tip of the causeway in February to find a Snowy Owl’s piercing yellow eyes staring at me is my idea of the essential experience of birding during a Vermont winter. Visitors should pay close attention to weather and wind conditions and forecasts before venturing out onto the causeway, particularly during winter.

At the end of a long birding day in Burlington, there is no better place to stop than the patio of Zero Gravity Brewery off Pine Street in Burlington’s arts district, the South End. While you sip a Bob White Belgian Wit, or a Bobolink Farmhouse Saison, you can scan the skies for Black-crowned Night-Herons or Common Nighthawks. During the winter, Burlington’s resident crows come in to their South End roost, swirling in cacophonous flocks of hundreds of birds descending on a single location to spend the night.

Good winter birding spots not included in this birding route are the Burlington Wastewater Treatment Plant on Riverside Avenue and many locations on the campus of University of Vermont. Along East Avenue across from Catamount Drive, there is a large group of birches and fruiting trees that have hosted flocks of Common Redpolls, Pine Grosbeaks, and Bohemian and Cedar waxwings during irruption years. Ornamental crabapples and hawthorns abound across campus and can be magnets for these brash visitors from the north. Walking any of the campus greens in winter, you can find the more common frugivores such as American Robins and Cedar Waxwings; exceptional years have seen high counts of 300 Bohemian Waxwings and 25 Pine Grosbeaks. Perhaps no visitor to campus drew more attention than the Snowy Owl in 2018, a significant irruption year for this species.

Although Burlington may lack the species that draw many birders to Vermont, such as the Bicknell’s Thrush of the Green Mountains or the Spruce Grouse of the Northeast Kingdom, it hosts a vast array of bird species in any season and is accessible, stunningly beautiful, fun to explore, and a necessary stop on any birder’s trip to the Green Mountain State. When you visit, be sure to report your sightings to Vermont eBird. Consider uploading photos of plants, fungi, insects, and wildlife to iNaturalist where they can be shared with the Vermont Atlas of Life. Whether your visit to Burlington coincides with the peak of spring migration or the coldest day of a Vermont winter, you are sure to find some exciting species. No matter what time of year you visit, the Ben & Jerry’s scoop shop will be open to celebrate in the event you found any life birds.

Nathaniel Sharp has been a birder and naturalist since the age of nine. Born and raised in the Philadelphia suburbs, he graduated from the University of Vermont in 2018 with a degree in Wildlife Biology. Currently working as a staff biologist at the Vermont Center for Ecostudies, he spends his field seasons banding Bicknell’s Thrushes on Mount Mansfield, netting rare bees in Vermont’s meadows, and convincing people that “iNaturalisting” and “eBirding” are verbs they should start using.